5500 BC / 3100 BC

prehistoric egypt

This period covers all of ancient Egyptian prehistory, from the Paleolithic (Old Stone Age), down to the end of the Neolithic (New Stone Age). Strictly speaking, “prehistory” refers to the phase of a culture before it had writing. In Egypt’s case, writing appears at around the same time as the end of its Stone Age, around 3100 BC. This is also when Egypt as a unified political entity came into being, making it the world’s oldest nation state

Before the formation of the first Egyptian state, during the Neolithic Period, an increasing homogenization of the different cultures that had emerged along the Nile Valley can be seen. Cultures are named after their sites of origin. Some of the most important of these are the Maadi Cultural Complex (c.4000–3100 BC) in Lower Egypt, near Cairo; Badarian culture (c.5500–4000 BC) near modern Asyut in Middle Egypt; and, most importantly Naqada I (c.4000–3500 BC) in Upper Egypt, near Luxor.

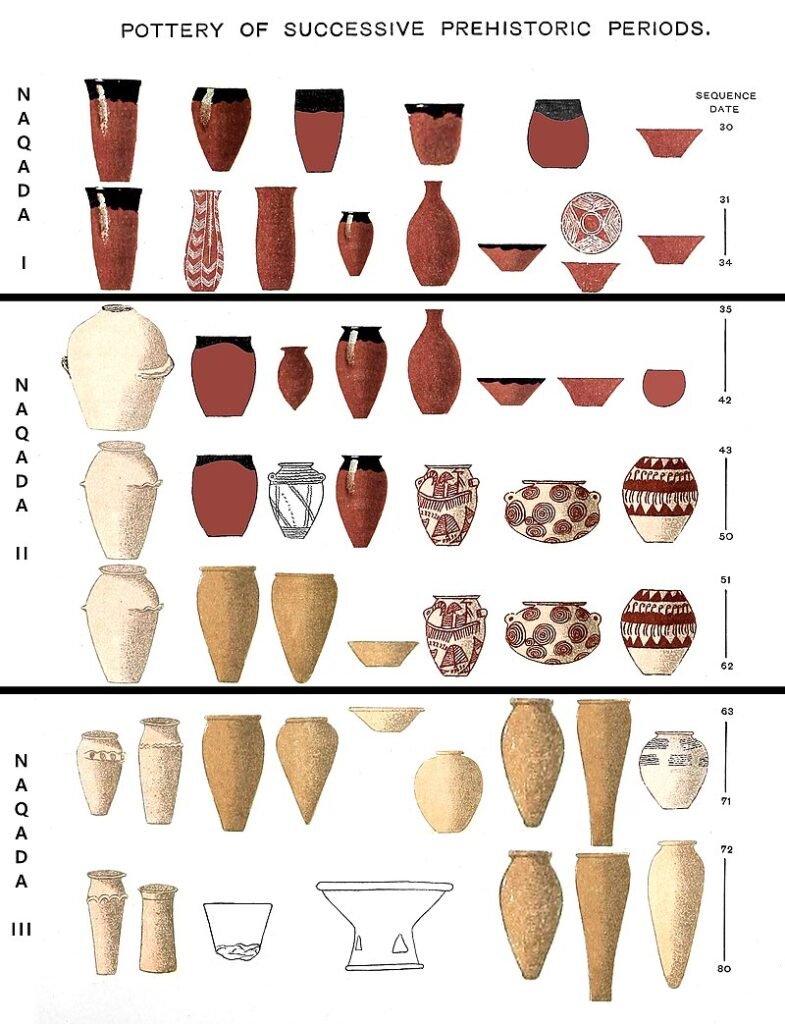

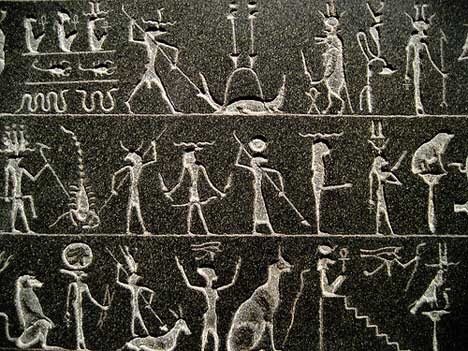

Naqada I culture, like its contemporaries, initially displays little in the way of social stratification, but this changes towards the end of this period. This trend became more pronounced during Naqada II (c.3500–3200 BC), which began to spread along the Nile Valley. Among the most important Naqada II sites, aside from Naqada itself, were Hierakonpolis (Kom al‑Ahmar), near Edfu, and Abydos, both in Upper Egypt. During Naqada III (c.3500–3100 BC), society continued to grow more complex, and differentiated itself from contemporary Nubian culture, eventually separating itself from it politically. The transition from Naqada III to the Early Dynastic Period was a smooth one. For this reason, Naqada III is sometimes also called “Dynasty 0”.

The powerful chiefs of this final period appear to have already been in control of most, if not all, of Egypt. Upper and Lower Egypt were geographically different, and the two had remained distinct until late in prehistory, and the ancient Egyptians never forgot this fact. Thus, when Egypt eventually became united as one political entity under a single ruler, the ancient Egyptians, throughout their entire history, referred to their king as the “Lord of the Two Lands”.

Badarian Culture

The Predynastic Period begins in the middle areas of Egypt with the so-called Badarian culture, a name given to group a series of archaeological sites – six hundred tombs with rich funerary equipment and forty little-investigated settlements – distributed over more than thirty kilometers of the eastern bank of the Nile.

At first it was thought that it was a culture restricted to the area that gives it its name, El Badari, but more recently objects very characteristic of it have been found in much more southern and eastern areas. Beyond its relevance as the first demonstration of the use of agriculture in Upper Egypt, the Badarian culture is known above all for its necropolis in the desert.

All the graves are simple oval holes in the ground that, in many cases, contain a mat on which the corpse is placed. In general, these bodies are in a not too hunched fetal position, lying on the left side, with the head directed south and facing west. Its rich funerary furnishings are striking, suggesting an unequal distribution of wealth and, therefore, the existence of a certain social stratification. This thesis is further reinforced by the fact that the richest tombs tend to separate from the others in specific areas of the necropolis.

Naqada I & II

The civilization or culture of Naqada was born shortly after in the time of the end of the Badarian culture and something more to the south. Specifically, it covers all the territories previously occupied by the Badarian plus the Thebes region, already in the middle of Upper Egypt.

This second great phase of the Predynastic period takes its name from the archaeological site of Naqada, where the famous Egyptologist Flinders Petrie discovered a huge cemetery of more than 3,000 graves in 1892. These burials consist of little more than the body in a fetal position on the left side, wrapped in animal skin, sometimes covered by a mat and deposited in simple oval holes dug in the sand. Compared with the important finds from the world of the dead, the preserved remains of the human settlements of Naqada I are poor and scarce.

The buildings, built using a mixture of mud and organic materials, have not been well preserved, so they have not been able to be well studied by archaeologists. This ignorance directly affects our understanding of the life forms of Naqada I, so that we can only theorize about them from other evidence, such as the presence of domestic animals in the grave goods: Goats, sheep and cattle.

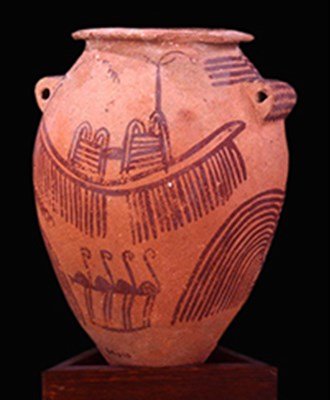

Naqada II is an evolution of everything already seen in the Nagada I culture, rather than an abrupt change or an independent culture. The Naqada civilization spread south to Nubia at the second cataract, and north to cover the entirety of Middle Egypt and come into contact with the Maadi culture in Lower Egypt.

In fact, around 3400 BC it continued its penetration towards the north, occupying the south and east of the Delta, even overlapping the Maadi culture itself. Finally, around 3300 BC, the culture of Naqada II is archaeologically documented throughout the Delta, thus achieving for the first time the cultural unification of all Egypt, centuries before political unification took place.

From this moment, the sedentary Egyptians experienced a rapid development of their civilization, all coinciding with the beginning of the exploitation of the quarries, the manufacture of pottery on the wheel, the decoration of the vessels with red paint, the appearance of the jewelry and copper metallurgy at full capacity and the manufacture of stone vessels. Likewise, the agricultural surpluses of the new locations stimulated the division of labor, social stratification and the evolution of the political system towards state forms.

Maadi Culture

Contemporary throughout its development to these three cultural phases, in Lower Egypt we first find the Maadian cultural complex, which is later joined by the Buto cultural complex in 3600 BC.

The Maadian specifically is made up of a dozen archaeological sites, among those that emphasize the cemetery and the establishment of the own Maadi. Contrary to what we see at the sites of the Naqada civilization, the Maadi cemeteries are much less important to the archaeological record than the settlements.

In this sense, the excavated structures show three types of remains, one of which is completely exceptional. It consists of houses excavated in the rock with oval plans measuring 3 x 5 meters in surface and up to three meters deep, which were accessed through an excavated passage.

The presence of hearths, semi-buried jugs and household remains suggests that they were permanent places of residence, which is not without attention for being underground. On the other side of the scale, around 600 tombs have been discovered in Maadi, which is nothing compared to the 15,000 predynastic tombs in the south of the country. It is not only a question of quantity, but also of quality: the tombs of Lower Egypt are extremely simple, based on oval holes with the deceased in a fetal position, wrapped in a mat or cloth and accompanied only by one or two ceramic containers or even for nothing at all.

Starting in 3600 BC, the Maadi-Buto culture not only had contact with the civilization of Naqada II to the south, but was also related to Asia by land with the Palestinian strip and by sea with the northern coast of Syria and, through it, with Mesopotamia.

Merimde Beni Salama

Merimde Beni Salama is a major Neolithic settlement site on the western margin of the Delta, about 60km north-west of Cairo. The site is the largest and earliest known evidence of settlement in the Nile Valley or Delta region and has been given the name ‘Merimde’, which is the phase of Lower Egyptian Predynastic culture.

It was found in 1928 by German archaeologist Herman Junker who excavated the site throughout 1939. Through carbon dating, the site was occupied between 4880BC and 4250BC. Unfortunately, most of Junker’s notes were destroyed in World War II. Eiwanger has conducted more recent studies.

The earliest level is characterised by a wide range of polished and unpolished untemper pottery decorated with a herringbone design. The Middle Merimde level shows complex structures of wood and basketwork, straw-tempered pottery and many burials. Flint tools inserted into wooden, bone and ivory handles were also found.

The later level of the Classic Merimde, considered the period of occupation, is when the settlement consisted of a large village of mud huts and workspaces in organised groups of buildings laid out in streets. The high level of organisation in the villages, indicated by numerous subterranean silos or granaries, lined with basketware and used to store grain, are probably associated with individual dwellings. The suggestion is that by the later phases the population consisted of economically independent family groups in a formalised village life.